Charles Wales Drysdale and the Kootenay River Tragedy

Foreword

There is a tree just within the southern boundary of Kootenay National Park on which is carved a commemoration to my grandfather days after he was lost in the Kootenay River. Having looked through pictures and documents I am fairly certain within 50 feet where that tree is located. Something that has never been found by the family and I would very much like to find it.

Charles Wales Drysdale's Kootenay Expedition

|

| Dr. Charles Wales Drysdale, Yale 1909. |

Charles Wales Drysdale, after whom Mt. Drysdale in Kootenay National Park is named, perished on a Geological Survey expedition along the Kootenay River in 1917. His body was never recovered nor the body of "Billy" Gray, Drysdale's field assistant who had accompanied him on many of his expeditions. The tragedy occurred three miles above the junction where the Cross River flows in the Kootenay River, just inside the southern boundary of Kootenay National Park.

The three maps below indicate the location of the incident. I established the location from a letter written by Lancaster D. Burling, a surviving member of this expedition, and also by carefully examining the accompanying photographs. In addition to the maps I have annotated below, there is a transcript of the letter written to my Grandmother by Lancaster D. Burling (and a link to the original), a link to the memorial published in 1918 by J. Austin Bancroft, and the series of photographs the survivors used to document what had happened. There are also a few photographs of the expedition's passage through Whiteman's Pass which rises to 2149m before descending through the Cross River valley to the Kootenay River; also known as the Cross Pass. The original name was given by the First Nations after Father Jean de Smet used this pass in 1845. The Father build a "Cross of Peace" at the summit of the pass from which Cross Lake derives its name.

The Expedition set out on horseback from Cochrane Alberta on June 25 or 26th 1917, until they reached Canmore Alberta, where they turned up into the mountains at what is now known as Spray Lakes.

The Maps and Expedition Planning

|

| This map shows the location of the accident in relation to the two rivers and the Kootenay Park highway. |

The map below shows how the large gravel cliff drops straight into the river just three miles above the junction of the Cross River and the Kootenay River. This is the only cliff that fits the description in the letter on this part of the river and also matches the cliffs in photograph two. If you examine the topography above you will see the ridge in the background of the picture.

|

Highway on left and Cross River, at bottom right   |

|

| 2. Annotated Photograph from the expedition's camera |

Expeditions Photographs of the Crossing

|

| 1. Drysdale, Burling, and Smith "dressed" for the crossing of the Kootenay July 10th [1917], and getting this ready. Dotted arrow = direction rive is flowing in each case. |

|

| 2. X = first trip. Y = second, both starting from the same place, the island in the centre of picture see photograph 3 |

2019 Expedition

On August 29th, 2019 we parked two vehicles on Settlers Road at Silt Creek, the road itself is covered in dust from the large trucks leaving the Baymag mining operation. The dust filters into the forest for some distance. We used the phone GPS to locate where the Silt Creek would have passed under this road and at that point parked our cars at the side of the road on a bend where we could get out of the path of the large double trailered dump truck that comes barreling down the road every few minutes.

The GPS tracking, in the image below, marks in red our progress down the hill to the river. The forest here is littered with small trees that have been blown over leaving a constant crisscrossing of logs that have to be stepped over. When we finally did find some animal paths they were left by much smaller animals, as the branches above a few feet were undisturbed. So not the paths of bears or deer, we speculated given from the scat that we found that they were made by coyotes or wolfs. The descent to the river took perhaps an hour and a half.

The GPS tracking, in the image below, marks in red our progress down the hill to the river. The forest here is littered with small trees that have been blown over leaving a constant crisscrossing of logs that have to be stepped over. When we finally did find some animal paths they were left by much smaller animals, as the branches above a few feet were undisturbed. So not the paths of bears or deer, we speculated given from the scat that we found that they were made by coyotes or wolfs. The descent to the river took perhaps an hour and a half.

When we reach the river we came out below the cliff described in the Burling letter. You can see from the image below the full force of the river runs directly into a cleavage in the cliff that has been gouged out of the cliff face. Forcing the river to ricochet at right angles toward the other bank. The force of the river against the cliff appears capable of creating a deep well under the cliff. The 1917 expedition party describe it as follows: "soundings next morning showed a cut under the bank with very deep water and a terrible undertow." In the image below you can see how after this cliff the river becomes very shallow on this side, and the deeper flow of the river goes across to the other side.

The image below is taken from the cliff looking down river here you can see how the main flow of the river has moved to the other side of the river leaving the area to the right for logs and debris to come to rest in the shallower water.

The photograph below shows the area where the logs have gathered, and you can see there are still logjams there that have been stranded on the shore as the water level went down this summer.

Moving along the cliff we were able to locate the deep undercut described in the letter and it was exacting were we had pinpointed it in our expedition research. Searching the areas 25 feet from the cliff we came upon a large tree that appear in some what of a clear area with less debris around it.

As we examined the tree we noticed a partial buried cairn of stones against the base of the tree. The trees bark was extremely thick if the 1917 party only had a pen knife it would have been impossible for them to carve into the tree, they would have been forced to carve into the bark.

On the other side of the tree we did see a disturbed area of the tree as you can see in the image below, where the bark seems to have been disturbed.

Having found the tree exactly as described in the letter we took this photograph of the expedition party standing beside the tree. (left to right: Peter and Elise, Sandrine and Aaron, Edward, Malakai and Dahl.

At this point we decided to add to the existing cairn that was at the base of the tree, and began gathering rocks from the surrounding area.

Afterwords we walked further up the river from this tree through the woods to the embankment that leads down to the river on the other side we found the trail in the cliff that they must have run up. This animal trail is still there and having run up it you would have run directly into this tree, before turning to go to the edge of the cliff where the raft hit.

In the image below you can see what they would have seen from the cliff after rounding the tree and going to the cliffs edge. You can see from the first two pictures that the shallow area is very close to the cliffs edge so quite a bit of the river is under the cliff at this point. In the third shot you can see the disturbance create by this force agains the cliff.

The river in September is much lower, according to the locals who run the river with rafts the peak flow is June and July. So when the 1917 expedition reach the river it would have been at peak flow, making this point in the river quite dangerous.

This experience was quite emotional for me and others in the group to be in this place where our grandfather must still be resting. To see the description of the letter come to life in front of us and to think of how isolated they must have been in their grief as they searched from their lost friends, days away from any form of civilization.

Expeditions Photographs from 1917

|

| Left to right Gray, Smith and Drysdale. The road between Cochrane and Camrose Alberta at start of trip over Whitemans Pass. June 25th or 26th 1917. |

|

| Emmons (cook) and Smith (packer) |

Letter Written by Lancaster D. Burling to Mrs. Drysdale documenting the event.

Sinclair, P.O., B. O.,

12th July 1917

Dear Mrs. Drysdale:

It's midnight, and everything is quiet, and I am going to try and tell you all.

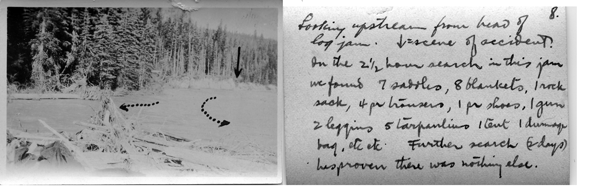

We spent Monday looking for a possible fording place but failed and decided to raft across. Tuesday we moved up the Kootenay River about three miles above where the Cross River empties into it, and decided to build a raft on an island that we could reach by fording, and left much less river to raft than if we had taken a sot where the whole river would have to be crossed. We built the raft of logs in the logjam at the upper end of island "f." It was wired and spiked, 16 feet long by 8 feet wide, made of logs 10 inches or over in diameter, a staunch craft which struck a log at the head of the island "f" on the return without hurting it, and struck the cliff at "z" and capsized without hurting it, on the second trip across. Our packer, George M. Smith, who had rafted many times and our most experienced man, was practically in charge of the raft on both trips by common consent. We were all on the island, and all helped build the raft, loaded it, lashing everything to the raft and Smith and your husband decided to make the first trip. I shoved the raft off with an 18-foot pole, going into the water about 20 feet and your husband, or the "chief" as he was affectionately called by the packer, (Smith) jumped ashore at "b" with the rope. He had difficulty holding the raft and Smith jumped also and swung it into shore, a perfect crossing. The safety zone, or place along any part of which a safe landing could be made extended 900 feet below where they stopped so we all felt that perfect safety for the second trip was assured. I crossed on one of the horses and made it after a long hard swim, in which I was proud of him, hitting the bank above "b." The three of us then lined the raft back up the to "g." a long very hard trip with Smith in his stocking feet. Your husband and myself, had kept our shoes on even though we expected that we might have to swim for it. Since "the Chief" was chief of the party and felt that he should be with the main outfit and since he and Smith had already made one safe trip I was left on the far side of the river to catch the rope on the second trip and thus save either of them from having to jump again after the exertion of paddling across, and they crossed back. I still think it was wise, they crossed safely, knew the raft and the river and a freshman was on hand to catch the rope, and we saw no chance of failure.

I was able to give the raft a good 35 foot push-off, and they made the head of our island but struck the jam hard enough so that the raft tipped upon its side in the current and when they righted it the raft was floating upside down. It was absolutely unhurt so they spiked new pieces across it and loaded on the rest of the material. The horses were then sent across with Emmons, the cook on the first horse. He and all the horses made the trip safely, though two of the horses were very poor swimmers. Perhaps I should mention that we were all in our underwear except your husband who kept on his breeches and the cook who kept on only his shirt and even took off is hobnailed boots. As things turned out he would have been unable to offer any assistance if he had been there by the absence of some clothing made it impossible for him to stand the cold water and the absence of boots made him slower in reaching the cliffs than I who had kept them on, but for the same reason placed him in a position to see what happened. He reached the west side of the river in time to stand with me at "b" ready to catch the rope (two lash ropes tied together) from the raft. I had spent the meantime getting acquainted with the bottom, the water was very muddy, depth of water, etc., below "b" so that there should be no failure from our stepping into a deep hole and being pulled off our feet. The raft started with your husband, Gray his assistant, and Smith (and our little stray dog Gyp, who had joined us at Canmore and had climbed every hill with us, swam those fords where we didn't lift him into one of our saddles, shared our lunches and our beds, (he insisted on being inside and usually slept with Gray). But there was no one to push it off, a disadvantage which I immediately assumed would be more than offset by the presence of an extra man to paddle, but the raft never got into the current that would have swung it toward the shore from "b" to "b" 1. They were way beyond the reach of ropes though we selected the proven shallowest portion and went to the farthest possible depth. They were paddling strong, however, and there was still 900 feet of good landing below so I ran down the bank to "b" 1 keeping opposite them. Shortly before they reach that point they realized they never could make it, they were still almost in mid-current and started to paddle away from the shore in order not to be carried against the cliffs. In this, they were too late, and the raft struck the cliff at "a" just alongside of a little inlet. If it had struck about twenty feet further down the inlet (another one) at that point was just so fixed that they probably could have saved themselves and easily waited for us to help them climb the cliff. Your husband jumped for this inlet, followed immediately by his assistant, and that instant I saw a foot splash the water as if one of them were swimming hard to keep in the inlet. It all happened so suddenly that it seemed as if I were looking down from above with a pole in my hand tens seconds later, but the cook estimated the time at a minute and a half or possibly more when I asked the next morning. We went over the ground and I ran 80 feet swam 5 feet, crawled over a large spruce tree, swam 15 feet more, climbed the gravel cliff which fortunately was not as vertical as it usually weathers, about 20 feet high, and ran 60 feet picking up a pole with a branched end, which seemed to be providentially placed by my path, before I reached the spot. But they were gone, and by the way, the water swirled and shot under the cliff, I knew that they had been carried down. I ran to the next inlet, and the next, and then saw that Smith had saved himself and was watching the river for them. I could see the river near the cliffs and for several hundred yards downstream but neither Smith from the raft which he climbed aboard after it capsized or the bar "d" to which he jumped, nor the cook from his position upstream where he could see into the inlet, nor I from the top of the cliff ever saw either of them after that first splash. On the chance that they might have lodged in the logjam at the upper end of bar "d" we worked in the water there for two hours and a half. Written or spoken words couldn't convey our feelings then nor mine now.

We heard no outcry and they must have gone under immediately - soundings next morning showed a cut under the bank with very deep water and a terrible undertow. The cook told me today that he had followed me over the spruce log below the cliff and for some time was afraid he would go under himself. I had to tell him I was never conscious of the current when I swam it and only mention it now because it almost go him and it wasn't the fraction of a circumstance to the current that cut under from the inlet the boys jumped into. They hadn't a single chance. Both your husband and his assistant must have lost consciousness immediately, the time was one of instant rather than seconds, and we after the shock of almost unbelievable suddenness looked to this as the one ray of light in a picture that is so gloomy that my pen falters.

We kept hoping, or expecting to hear a call from somewhere, it didn't seem possible, and when two and half hours had gone by (the cook's watch came over safely) without finding what we were hoping against hope we would find soon enough it was a sorry little party that huddled around the material we had saved, found a waterproof match safe, and built a fire. It was getting dark, and I only gave the work to stop when it seemed certain that they were not caught in the logs and when it seemed too probable that in our thoroughly chilled condition a misstep in the treacherous swiftness that swept around and under the logjam would but add another to the toll.

We were up before sunrise, and after spending five hours on the jam without success, we came back to the spot where we had seen the last of our comrades and left the following record on a large spruce tree 25 feet back from the edge of the cliff.

____________________________

C. W. Drysdale

W. J. Gray

July 10/17

Thirty miles trail the nearest settlement, in the heart of the mountains he loved, three bareheaded men by the side of a rude record made by their only rescued instrument, a jackknife, asked God to bless Mr. and Mrs. Gray and yourself and your dear children. I can't write anymore.

Signed

Lancaster D. Burling

I can't close without saying that I count it one of the privileges of my life to have gotten to know your husband and the men all felt the same.

This letter is so full of our little part, I am sorry.

Memorial of Charles Wales Drysdale

Mount Drysdale

Mount Drysdale is located to the South of Mount Goodsir in the Vermillion Range directly NW of Wolverine Pass. Wolverine pass separates Mount Gray from Mount Drysdale.

The Two Sons

Drysdale, William, Bookseller, Montreal, was born in the city of Montreal on the 17th of April, 1847. His father, Adam Drysdale, was a native of Dunfermline, Scotland, settled in Canada many years ago, and for a long time held a position in the civil service of Canada, conferred upon him by the late Lord Elgin. His grandfather was one of the first persons to engage in the shipping trade between Scotland and Canada, especially to the port of Montreal. William Drysdale was educated at Montreal, entered into the book publishing which services Canada from the Gaspe to British Columbia. He published a number of important Canadian works that are of great value, in a historical sense, to the country at large. He was married in 1888 to Mary Mathie Wales, daughter of the late Charles Wales, merchant, of St. Andrews East.

Mary and William had three children William, Charles, and Mary. Mary, unfortunately, died at the age of one. The eldest son William worked for the American Locomotive Company in Schenectady, New York (which was eventually merged into The General Electic Company) and then went on to become the Vice President of Montreal Locomotive Works Ltd Montreal (which was eventually merge into Bomardier), he was also a wartime Director of munitions production.

His younger son Charles attended Yale University and obtain a Doctorate in Geology, he joined the Geological Survey of Canada and during WW I became the lead geologist surveying the mines of British Columbia.

|

| Montreal Publisher William Drysdale, with his two sons. William Flockhart Drysdale O.B.E. to his right and Dr. Charles Wales Drysdale to his left. |

Bibliography

Drysdale, C. W. (1913) Transcontinental Excursion C1, Part II Toronto to Victoria and return: Canadian Geological Survey, Guide Book No. 8, 243.

Delegate to the "International Geological Congress, 12th, Toronto. (1913)

Drysdale, C. W. (1915) "Geology of Franklin Mining Camp, British Columbia," Canadian Geological Survey Mem. 56.

Drysdale C. W. (1915) Geology and Ore Deposits of Rossland, British Columbia, Geological Survey of Canada, Memoir 77 (Ottawa: Government Printing Bureau)

Drysdale, C. W. (1915) Notes on the geology of the Molly molybdeminte mine, Lost Creek, Nelson mining division, B. C.: Canadian Min. Inst. Trans, vol. 18 pp. 247-255.

Drysdale, C. W. (1915): Geology and Ore Deposits of Rossland, British Columbia, Geological Survey of Canada, Mem. 77. (Attached Maps)

Drysdale, C. W. (1916): Bridge River Map-area, Lillooet Mining Division, Geological Survey, Canada, Summary Report. Page 75 of Report.

Drysdale, C. W. (1917) Ymir mining camp: Geological Survey of Canada Memoir 94.

Drysdale, C. W. (1912) "Geology of the Thompson River Valley below Kamloops Lake," Summary Report, Part A,

I am pleased that you have documented this so well with all the details and all the pieces of information that have been left to us about this man, his family and the tragedy. Thank-you Edward!

ReplyDeleteThank you Edward for the tremendous work you have done with this! It is an impressive amount of historical detective work. I hope that you are able to locate the monument tree.

ReplyDeleteIt was great to able to get a party of family together to be able to get down to river to experience what we have all been reading in a letter for so many years!

ReplyDelete